Letters from Dr. Moloney to Gaston Ramon:

Toronto April 8, 1928

My Dear Friend,

I am enclosing a short note with the letters of my family. Let me thank you and Madame Ramon for the beautiful books which my children have received (Les Chateaux de France).

Fraser will soon have the pleasure of seeing you in your laboratory. Before his departure we were busy with the papers for the Pasteur Annales. I appreciate very much this opportunity and I trust that some of these at least will be satisfactory.

I hope that you and your family are well. Give my regards to Madame Ramon.

Sincerely,

P. J. Moloney

March 22, 1932

My Dear Friend,

I regret that there has been some delay in sending you a report of the meeting of the American Public Health Assoc. held in Montreal last September. There are no published abstracts of the papers which were given. I am sending you under separate cover the Program and in addition a copy of the journal which contains papers on diphtheria. If there is any additional information which I could send to you do not hesitate to write.

Have you published anywhere a detailed account of the discovery of flocculation and anatoxine. I remember very well that you once gave me these details verbally-the setting up of mixtures of toxin and antitoxin for subcutaneous test on guinea pigs-the appearance of turbidity in certain of the mixtures-the thought that this might be infection-the resetting up of the test-the same phenomenon-the neutrality of the tube which first showed turbidity-later the addition of formalin as a convenient preservative-the discovery of its detoxifying action.

We would like very much here at the Connaught laboratiories if you could sometime publish these historical details of your discovery. They illustrate those words of Pasteur concerning the conditions required for a discovery, namely: "Chance in the prepared mind."

Thanks for the reprint which I received.

With kind regards,

Sincerely,

P. J. Moloney

March 23 1932

P. S.

I have just now received your letter in which you have referred to the matter of ear tags for guinea pigs and rabbits. Thank you very kindly for having ordered some for me. In a later letter I shall ask regarding the price of these.

Once again best wishes to you and to your family.

P. J. Moloney

April 9 1932

My Dear Friend,

Thanks very much for the ear tags and prices which have arrived. We have tried these out on guinea pigs and they are excellent. We have written to the company in Paris for a catalogue and prices in order to obtain a further supply. When these arrive Mr. Hutchison will write to you.

Once again let me thank you for your kindness. Best wishes to you and to your family.

Yours sincerely,

P. J. Moloney

Letters Courtesy of Institut Pasteur/Service des Archives

An undated letter written by E. Peter McDougall, son of Donald McDougall who was a friend of Dr. Moloney. Donald, blinded in WWI, went on to become the first blind Rhodes scholar at Oxford University and a Professor of History at University of Toronto; Dr. Moloney taught him geometry on Saturday walks.

"Peter Moloney, a lifelong friend of my father, is my Godfather. My first recollections of him are as a young boy. I was always delighted with his visits to our house in Toronto, because he always presented me with interesting and intriguing mathematical puzzles to play with. I also well remember several occasions on which my father, Peter Moloney, my brother and myself attended Maple Leaf baseball games.

My contact with Peter Moloney resumed after my childhood and University training in medicine when I returned to the surgical staff of St. Michael's Hospital. It was during my University days in medicine, that I first realized the magnitude of Dr. Moloney's contributions in my chosen profession. His achievements in the fields of the treatment and prophylaxis of tetanus, diphtheria, and diabetes have provided immense advancement in the treatment of these disorders.

In spite of the acclaim that he has received internationally for this work, he remains humble and unassuming.

I find in our periodic meetings now, that he continues his investigative approach to many medical problems with the enthusiasm of a man much younger.

I am proud and humbled in having such a man as my Godfather."

-- E. Peter McDougall

Agnes McDougall, the mother of E. Peter McDougall, and niece of the Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote this account of Dr. Moloney in 1981. She had been a nurse at St. Dunstan's hospital in England when Donald McDougall, a former POW who had been blinded was placed there. Patients could request a reader at any time and Agnes read to him. After Donald established himself in Toronto, he returned to England to marry her. They were lifelong friends of Dr. Moloney.

I first met Peter Moloney in 1932, soon after my arrival in this country. He and my husband had been friends for some years. They came from similar backgrounds and were both boarders at St. Michael's school. They never had much contact there as Peter was, I think, two years senior to my husband and thereafter their careers diverged widely but eventually brought them both to the University of Toronto, where my husband taught history. Though the subjects with which they were concerned were very different they were both men of wide interests and had much in common. My first meeting with Peter is still vivid in my memory. He impressed me as by far the most interesting person I had met since coming to Canada. I was struck by his refreshing outlook on life, with his tremendous interest and curiosity about everything and withal his complete naturalness and simplicity, all of which characteristics remain true of him to this day, 49 years later in spite of all the successful work he has accomplished and the many honours he has received. During his many subsequent visits to us over the years, it was always a pleasure to listen to the conversation between him and my husband as they both had a great sense of humour and Peter was always coming up with new ideas and puzzles, which often being mathematical were beyond my comprehension but none the less intriguing. Not long after this first meeting, Peter took us out to Scarborough, it was quite in the country, where they were living. They were a most interesting family, very happy and informal, the children were ranging in age from two years to about 13. They boys were already showing the skill which they continued to develop in handicrafts. Later I remember a splendid boat which they built in their garage, and beautifully fashioned bows and arrows. It was evident that they began this art in early life, as Peter, their two and a half, was already whittling away at a stick with a pocket knife, without, to my astonishment, either injuring himself or being expected to do so by his elders. When years later, the Moloneys moved to Toronto, we were and still are not far from each other as we were all in St. Basil's parish, and so our meetings were more frequent. I now realize how very little I knew of the number of discoveries which Peter had made, or had a part in making, or of the number of honours he had received. I suppose our sons were among the first recipients of his diphtheira toxoid, and we were aware of his work on anti-tetanus serum during the war, and later of that on diabetes, when he was given his LL. D., at which we were present. He did occasionally mention having been asked to read papers or join in conferences of fellow scientists in Europe, but he has remained so unassuming that no one would suspect the extent of his achievements. It has indeed been a privilege and a happiness to have known him over all these years.

--Agnes McDougall

Alice Gibb taught Classics at St. Joseph High School, Toronto and became a family friend of the Moloneys. She tells of the blind war veteran whom Dr. Moloney tutored. In her letter we are given a rare glimpse of the family life and character of Dr. Moloney, available in no other source.

In the fifties I came to live, for a short time, with Dr. Moloney and his wife in their home on St. Mary Street. When I think of them, an endearing picture of happy, married life always comes to mind. I see them sitting side by side, on a sofa, after dinner, before a blazing log fire, with Mrs. Moloney reading aloud from the novels of Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollop, two of her husband's favourite authors.

I had only been with them a few days when I became aware of Dr. Moloney's great love of the French language. Many a Sunday morning the French instructor from St. Michael's College would come for breakfast and give him and his wife a lesson in French. It was first class French "immersion". No English was ever spoken. The method worked: Doctor Moloney became so proficient in French that he was able to give a paper in French to a National Medical Convention in Quebec City. Once I asked him why he and his wife were so keen on learning French; he said that they considered this to be their contribution to Canadian unity. and this was way back in the fifties, at a time when many of us were scarcely aware of a problem of Canadian unity.

All languages seemed to have a fascination for him and he set himself the task of learning the "Ave Maria" in Latin, French, Spanish, German, Arabic and Gaelic. He was attracted to Arabic because his wife's people had come from Andalusia, Spain, and he thought that probably his children had some Arabic blood.

Mrs. Moloney told me that, during the war, her husband had bought some government bonds, but to the amazement of the government, would accept no interest, because "the country was at war". The Minister of Finance wrote a letter of thanks and asked permission to publicize the patriotic gesture in the hope of inspiring other Canadians to imitate his example. As Dr. Moloney always shunned publicity, I do not think this permission was ever given.

After the war, Dr. Moloney helped a veteran, who had been blinded in active service, obtain his Grade XIII (as it was then called). I always wondered how he could teach a blind man geometry. How would he know whether his pupil understood the geometry propositions? "Oh, that was easy," he said. "His whole face would light up and I would know immediately that he understood." That student graduated from university and, as a Rhodes Scholar, went to Oxford. Later he returned to Canada and became a renowned professor of Canadian History at the University of Toronto.

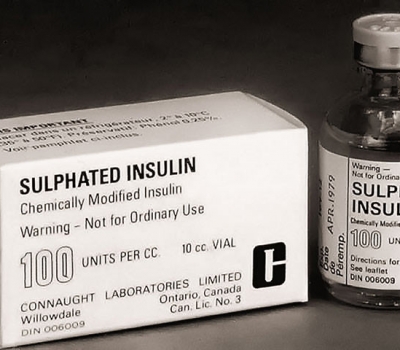

Dr. Moloney was always intensely interested in all aspects of his work but it was the human aspect in which he took a special delight. I think that is why his work with sulphated insulin especially appealed to him. He could see the immediate results on human beings. Sulphated insulin, which is effective in insulin-resistant diabetics was discovered in Dr. Moloney's "lab". At first, the Connaught Lab was the only place where sulphated insulin was produced. From all over the country long distance calls would come from doctors begging for an immediate supply of this insulin. To save the patient's life he had to receive the insulin at once. I can vividly see Dr. Moloney rushing out to the airport late at night with this insulin and thus ensuring its shipment as soon as possible.

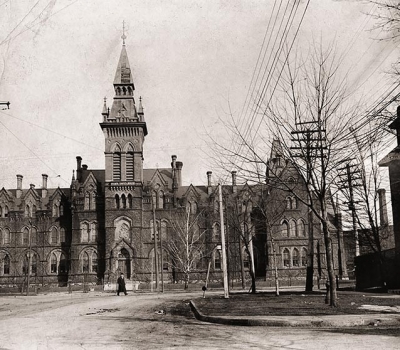

As a young boy Dr. Moloney was a boarder at St. Michael's College School. Early in the morning, the boys would go outside for exercise. He often tells how he would look up at the lighted homes on St. Mary Street and think, "Some day I would like to live there". And he did. For many years his home was on St. Mary Street. A few years after his wife died he moved from there and lived at St. Michael's College where he is still living today. And thus the full cycle of his life with St. Michael's College is being completed.-Alice Gibbs

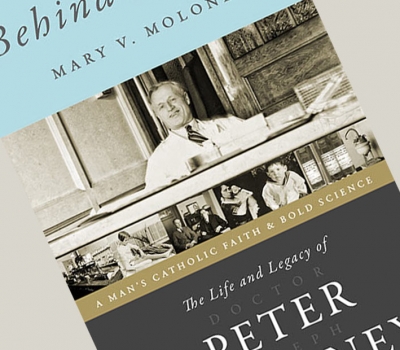

Dr. Lou Goldsmith, who received his Ph. D. under Dr. Moloney in 1955, discovered the web presence of Dr. Moloney in early summer of 2011. His letters bring out the sterling character of his early mentor.

From Lou Goldsmith, Monday, July 4, 2011:

"I was a graduate student with Dr. Moloney until I received my Ph. D. in 1955 "Chemical and Immunological Studies on Insulins". Recently I searched online for more information about him because I wanted to pass on to my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren details about the person that had played such an important role in my education and my life while I can - am now 82 years old...

When I started working with him he asked me to read a book, I believe it was titled "Science is a Sacred Cow". Essentially it said-always seek proof-just because something is printed in a textbook does not mean that it is actually true. That principle and many others that I learned from him have guided me throughout my life. Even though I moved to the U. S. we corresponded until he passed away.

Dr. Moloney was probably the single most influential person in my life and I will never forget him."

From Lou Goldsmith, Wednesday, July 6, 2011:

"Dr. Moloney was an accomplished researcher but he had a very practical side and worked on many projects that improved public health and undoubtedly saved many lives. You may be interested in how I came to work with him. In 1950 I had just completed my junior year in Chemical Engineering (CE) when I got a summer job at Connaught. Because of what I saw, I became very interested in biochemical as well as chemical topics. In the senior year of CE each student has to take on a thesis subject-usually the standard topics. in CE. I asked my department head if it would be possible for me to study a biochemical topic instead. He liked the idea and called Dr. Moloney to set it up. So he became my thesis advisor while I was still an undergraduate. That led to me doing my Masters thesis with him as well and finally my Ph. D. I became a "biochemical engineer" before that term had even been invented.

When I moved to the U.S. (because I was unable to find a suitable position in Canada) I worked first for an animal feed products company making vitamins and antibiotics by chemical and microbiological processes and then a pharmaceutical company producing drugs and other products (e.g. the sweetener Nutrasweet) again by chemical and microbiological processes. I continued my interest in research but mostly I worked in technical manufaturing, scaling up new processes to make them work on a very large scale. It was using applied science, another one of the valuable lessons that I had learned from your grandfather."

From Lou Goldsmith, Friday, July 15, 2011:

"I remembered another example of your grandfather's goodness. Do you know about the Connaught's contribution to the development of the Salk polio vaccine? It is described in the two pages that are attached. That article does not mention Dr. Moloney but he was very likely involved because of his expertise in immunology. Late in 1953, he arranged for my wife, who was pregnant, to received the Salk vaccine, long before it was generally available. She was probably the first pregnant woman to be innoculated. Our first son was born in Feb. 1954 and was probably the first fetus to receive the vaccine."

From Lou Goldsmith, Sunday, July 24, 2011:

"I found this marvellous letter that I want you to see right away. My wife and I were married in June, 1952 while I was still studying for my Master's degree. We invited your grandfather and grandmother and the Tosonis. From his comments, I guess your grandfather had never been to a Jewish wedding before. What is amazing is that he was 95 when he wrote this letter, remembering many details from almost 35 years earlier.

In his usual gracious manner, he called me a colleague when I was actually his student."

From Peter Moloney to Dr. Sydney Cook, May 26, 1984

You brought me back to 1914 and I will address you as you would have addressed me then, and I hope now. None of us knew one another by our first names. And so:

Dear Cook,

It was a pleasure for me to receive your letter and to hear about your successful life and particularly that you are still working.

I had graduated in Arts before I entered chemistry and as a result I was permitted to omit most Arts subjects. Under Professor Kenrich I worked on a research problem for which I was granted an M. A. in chemistry.

Three of us were granted scholarships at Berkeley University of California. After a year I married a girl whom I had met at the University. I obtained a job at the Cutter Laboratories as chemist. I had excellent prospects. But the War was on and I was anxious to return to Canada, not that I intended enlisting but I wanted to be in Canada in case I were called up. I was offered work in the Department of Agriculture in a laboratory on Carling Avenue. In 1919 I was offered work at the Connaught Laboratories and resigned from Ottawa. I was a full-time worker with Connaught until 1963, and as a consultant until 1981. My good wife died in 1963; it was a great loss and one I still suffer. We had five wonderful children, all living, three married ones with families.

Once again I congratulate you on your good life. And with the best of good wishes

Sincerely,

Moloney

St. Mark's College,

5960 Chancellor Blvd.

Vancouver, B. C. Nov. 29, 62.

Dear Peter,

Fabre, the great French scientist, tells a story of a wasp that used to have to perform an operation on a caterpillar, that would paralyze it but not kill it. You know the story. Windle used to tell it. I have never forgotten it. Every detail of the story demands God. The most amazing part of the story as Windle told it was that the wasp had to perform that operation without any experience and it was so delicate that eminent surgeons told him they could not dare attempt it without much experience. And the wasp never failed.

Now here is where you come in. I have had in mind for years to write you this letter. I would like many scientific examples like that in nature, in animals and in plant life. You must have a store of them beyond number. There is an example in the paper every day dealing with the lives of animal usually and sometimes of plants too, which show God working in nature. I would like to make a collection of them. And I am appealing to you for examples, not one or two or ten, but hundreds. Regards to Mrs. and all. I pray for all of you every day.

In Our Lord,

H. Carr, C. S. B.

A personal note to Dr. Peter Moloney from Dr. Charles H. Best, with a scene from an original painting by Best named "Wind in the Pines"