In 1974, the University of Toronto's Elizabeth Wilson interviewed Dr. Peter Moloney as part of its Oral History Programme on January 21, 1974, when he was 83 years old. These are the original recordings.

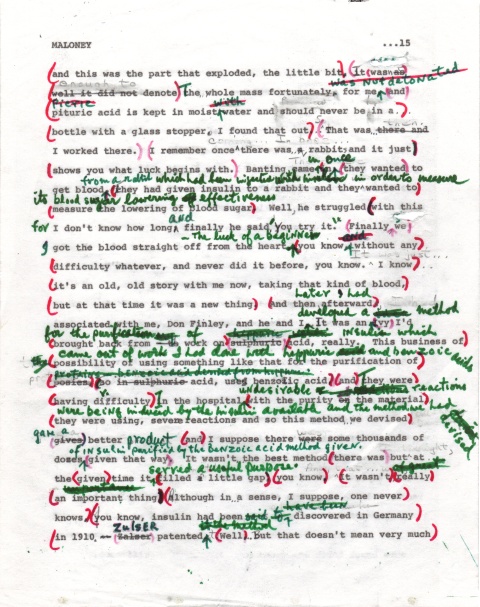

The transcript, including Dr. Moloney's editing, is available here for the first time.

The audio recording is made available courtesy of University of Toronto Archives: Peter Joseph Moloney B74-0039.

Read the transcript of the interview

I remember on one occasion Banting came into the Lab to take blood from a rabbit which had been injected with insulin..."

Dr. Moloney was interviewed and recorded on tape recorder by Elizabeth Wilson of the University of Toronto Oral History Programme on January 21, 1974, when he was 83 years old. The original text including Dr. Moloney's editing is published here for the first time.

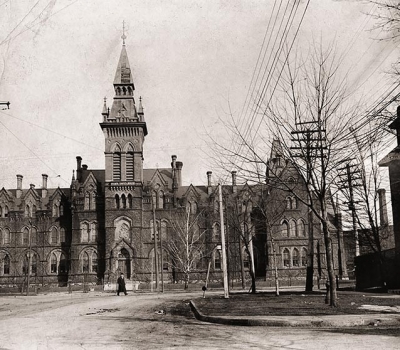

In a letter from the archivist, he was asked only to correct spelling or errors of fact, not alter the substance of his remarks or grammar errors, as such changes would be deemed to detract from the spontaneity of his replies. Many of his corrections were not published. Wilson wrote: "As part of the Oral History Programme of the University of Toronto, I am interviewing Dr. Peter Moloney in his office at Connaught Labs on Spadina Avenue. The date is January 21, 1974." On the envelope containing the transcript Wilson's wrote her opinion of the interview: "constrained, disastrous".

W: Dr. Moloney, let's start off with me asking you what made you decide first to come to the University of Toronto.

M: Well it wasn't really the University of Toronto at the beginning. I came from Powassan, a small town, and we didn't have a high school there. I owe a great deal to a man, the principal of the small public school-Mr. Coombs. We were poor people in general in the district, and there was no high school so Mr Coombs introduced what was called at that time a Continuation School, in which high school subjects without Latin or French or German were taught.

I finished there and then I had a chance to go to St. Michael's College to finish high school which I did. I repeated the last year of high school. It was rather natural then that I go on and enter the Arts Course which I did at St. Michael's College, and finished the Arts Course in that College. In a sense I have answered your question why I came to Toronto.

W: Yes. Yes. What did you study in your Arts programme?

M: Well, it was a General Arts Course. There were subjects such as English, Mathematics, French, Latin, and some Philosophy.

W: Well, what percentage of your classes did you take at St. Mike's and what percentage at the University?

M: I would say, it seems to me, about 80 % at St. Michael's. We had, for example, in the University, Professor Alexander and Professor Wallace for English, and Professor Dawes for Physics, and Professor James Mavor for Economics, and I'm not sure about Professor Ramsey Wright in Biology. He may have come later.

W: What year did you start your undergraduate courses?

M: 1908 and I graduated in 1912.

W: Hold on just a minute, can I stay in that area for a minute?

M: Yes, sure.

W: What subjects did you take in the University?

M: Well, you mean apart from St. Michael's College?

W: Other than St. Michael's, yes.

M: Economics, English, not all English, and physics and economics. Now I'm a little confused at the moment. I wanted always Experimental Science which I didn't have. And so I decided to go into Chemistry after graduation. It may have been then that I had Professor Ramsey Wright in Biology.

W: So you started to do an M. A. in Chemistry.

M: Yes I did.

W: Who did you work with at the time?

M: Professor Kendrick in Chemistry. He was a marvelous man, Professor Kendrick, and I must say about the Chemistry department one could hardly imagine more generous treatment. When I came I hadn't had any undergraduate Chemistry. Professor Miller, Professor of Physical Chemistry was the Head, a wonderful man. Professor Kendrick, I would rate very high intellectually, Professor Allan, Professor of Organic Chemistry was a good man. For me all red tape was cut. I didn't have to take the complete Chemistry course. My work was directed strictly to Chemistry and Mathematics. I had Professor Sam Beatty in Mathematics. Professor Kendrick directed the work of my M. A. thesis.

W. How many graduate students were there doing that work at the same time?

M: I think there could have been maybe four or five, I'm not sure. There weren't many.

W. How many courses were you taking?

M: Well that's a difficult question, in a way...courses. Mainly it was the subjects that concerned Chemistry - Physical Chemistry, and Organic Chemistry, Biology, and Mathematics. But coming back to Professor Kendrick again, a very unique man. He was a man who could be considered one of the poorest lecturers in the University of Toronto. I've heard other men later on in life referring to him as a buffoon. He was anything but that. He was an extraordinarily cultured man. And he was a man who was a martyr almost to a certain type of pedagogy. For example, he held that Chemistry was not a teachable subject, it was something to be struggled with. And I think he was perfectly right. Now, Professor Ramsey Wright was a very outstanding man. There is a building named for him, or was. As for Ramsey Wright the boys said that he could sing songs in Greek and swim like a fish. He spoke well, and he'd illustrate extraordinarily well with diagrams with coloured chalk. But I can tell you all I learned from him almost in a word and that is that sometimes one finds a pearl in a freshwater clam, that's all. In Economics, we had Professor Mavor a well-known figure. He had a rich Scottish accent and he seemed to be in a rather abstracted state a good part of the time. He would begin his lectures each day with "In my last lecture". Not only that but "six months ago when I was in Siberia" or then it might be "six months ago when I was in Mongolia". I mean this literally six months ago, it didn't matter where.

W: And it could have been five years ago?

M: Oh, it could have been anything, you see. Well, I remember on one occasion he wanted to tell us that in China it was necessary to enrich the land with human excreta. Well, there was the good old 19th century mind, and to his alarm there was a woman in the class. The woman was afterwards Mrs. Bott. I wonder if she is still living, the wife of Professor Bott. He was Professor of Psychology.

W: I don't know.

M: But, I think Professor Mavor was a little stumped how to tell us this, so what he did was, he said, "In China the land gets back its own." Well then in order to clarify the statement completely, and he was in real difficulty, all he could do was repeat, "In China the land gets back its own." And that's all the economics I remember. But, coming back to St. Michael's, we had at St. Michael's College an interesting life. I was always grateful to those men. They were really wonderful men.

W: Yes, well can you describe a bit of the life you had there? I'd be very interested in knowing.

M: Well, when I was a boy, a young boy coming there, there was a high school in the same quarters, in the same general area as there was university teaching. We were a lot of green little boys and I was horrified to find in the refectory, in the dining room, oh, by the way, we led a sort of monastic life, you know. It was forced on us. We had to get up at 5:30 in the morning. Then there were morning prayers, then study, then there was Chapel, Mass in the Chapel, then breakfast, school every day of the week, half days on Wednesday and Saturday. This is a good thing in the boarding school anyway. But we resented it. Naturally boys resent this sort of thing. But coming back to the time when I first came, there was in the refectory, the head table where the staff, mostly priests, not all but mostly priests sat, there were bottles of wine on the table. Now this was an old country French foundation, they had come over about '52, and there were still some old country Frenchman in the college and they were the ones that drank the wine, the others didn't, but I thought, wine! I came from what was called a Temperance District. It really wasn't temperance at all, it was total abstinence. Well in Powassan there was an old woman, I think her son drank heavily, who had organized a little group in which we'd sing a song which began "We'll turn our glasses upside down, and then in school we'd sing a patriotic song, "The wine cup, the wine cup bring hither, and fill, fill it true to the brim, may the wreath Nelson won never wither," and so on. Well, there was no clash of ideas at all for us as kids, but I thought, wine, you drank wine in the bar, and the purpose of a bar was that there be something to hang onto so that you wouldn't fall down. Well, there we were with this monastic type of life. The boys not only resented it, they exhibited a kind of roughness. But in reality they were a very wholesome lot of young fellows, I remember them very, very well. The authorities never attempted any kind of imposed table manners or things of that kind. If a boy wanted to transfer food to his mouth with his knife, including peas, if he were capable of the gymnastics, he would not be corrected by the staff. It might be that the boys would say something and you know the priests were perfectly right. We came from poor homes, and we could have gone back little snobs, some of us. There was no attempt to make fake little gentlemen of us. This is something I have thought of afterwards many times. These men were interested in our total welfare, to be good Christians, to be good men, and that we learn something. And we knew that , while we were temporarily there under discipline, they had chosen this discipline for life. A tremendous example for small boys or men of an unselfish act, and if you had occasion to speak to one of them, you'd think you were the only person in the school. And I think this business of unselfishness may have spilled over a little bit. You can teach it only by example and unselfishness is the very heart of good manners as it is of Christianity. It doesn't matter whether a table napkin is stuffed in the collar or in the top of the trousers or laid across the lap. This kind of drill can be part of a given culture. I'm glad there was no attempt to make little gentlemen out of us.

W: I just wanted to know if you ever had a chance to taste the wine or was it just...

M: Oh no.

M: Those of the staff who drank were old country men. I remember one man, who... couldn't speak English or didn't. He'd been stationed in North Africa, probably spoke Arabic. We wanted French conversation, but we were just a bunch of dumb bells. We made fun of him in class and finally it came through to him and the classes were dropped. Here were these old men, not that they were all old men, and while there wasn't any posing still there was a dignity about them. I never saw one even at 5:30 in the morning without starched white cuffs showing from the sleeve of his cassock. I remember with gratitude and affection the priests at St. Michael's College.

And at the head table, the way salad was prepared... We didn't have salad on our tables. There were no vitamins then, just food. There was a wooden bowl for salad, a custom from France, and the way they prepared the salad I remember years afterwards in the Connaught lunchroom for the senior Staff, a wooden salad bowl was purchased. I said to Dr. Fitzgerald why not prepare the salad as at St. Michael's College? "How was that?" Well, I told him. There were the materials for the salad, lettuce and what-not in the bowl but nothing was done with these until just before serving and then the oil and vinegar were put in and mixed. Dr. Fitzgerald was impressed and he said to me "Will you tell the others how it is done at St. Michael's College?" Well I remember the assumed roughness of the boys. I've told some of the old boys about this incident, which they enjoyed very much. As boys we tended to laugh at the customs of these old men. In reality they were very much a la page. They were men of dignity. There was scripture reading at meal time, for a short time - not every meal. At noon time, maybe noon and evening, I'm not sure.

W: Well Professor, did the vigorous regime you had as a high school student carry on through your university time too?

M: Oh yes, oh very much so. And not only that, you couldn't walk out, you know. You had to ask special permission, "and what's the purpose?" You might want to buy a celluloid collar or you might be allowed out for a couple of hours. I think there was a little relaxation during university life, but not very much. I am reminded of the days in Powassan and of Mr. Coombs, to him, we were a bunch of lazy wretches and he was a man of the rod. He wouldn't hesitate to strike. Fear can have a place in education. Mind you I must say we weren't really frightened of him. I am grateful to that man. Coming back to him for a moment, Mr. Coombs. When he began the continuation school, we had such things a Geometry, Trigonometry. He said, "Boys I haven't had these subjects, I'll have to study." The mark of a great man. And I became better in Geometry than he was. I had not the slightest feeling that I was superior to him, I was delighted, I thought it was a wonderful thing for him, and so did he. The Inspector would visit the school. He was keen about Euclidean Geometry and he'd propose a problem which hadn't been dealt with and I could solve the problem. And this reflected on the competency of the teacher and I was delighted. I used to have Mr. Coombs for lunch many times at the university. At the time he was Superintendent of Schools in Mimico.

W: When you finished your undergraduate time, did you stay at St. Michael's when you started doing your M. A.?

M: I stayed for half a year and then I quit. I went home. I thought I'd take a little time off. I took about half a year off and then I came back full time at the university until I had my M. A.

W: How long did that take?

M: Two and a half years.

W: What did you do your thesis in?

M: Well, it was a very interesting subject, something that proved useful afterwards. It was on a problem on solubility. One might think of it as a drab, dull subject but in reality it was fascinating - Do you know anything about solubility at all?

W: No.

M: Well if you take a crystal of say, barium sulphate or calcium sulphate and stir it in water, it will dissolve until a concentration is reached when no more will dissolve (barium and calcium sulphate are not very soluble in water). On the other hand if those substances are ground extremely finely, the solubility of the fine particles is greater than that of the unground crystal, that is the solution of the fine particles is supersaturated with respect to a large crystal, so that when such supersaturated solution is stirred with a large crystal its concentration decreases. And one might expect the concentration to decrease until it equaled that which is reached when a large crystal is stirred in water. I did not observe this even though stirring was continual for days (mechanical stirring day and night). Rates of reaction were slow. I was able to apply the idea of the solubility of small particles to the purification of diphtheria toxoid.

W: After you got your M. A. you then decided to ...

M: Well what happened after I got the M. A. was that three of us were offered bursaries to go to the University of California in Berkley. Three of us went out. I was there for a year. Well, what happened with me was I got married. I met my wife there, she was a university student. We were married there. But I was anxious to get back because the war was on. I had no intention of volunteering but I wanted to be here in case I was called up and so I came back.

W: You wanted to be called up.

M: No, I didn't. No I wasn't going to volunteer, but I thought in case I'm called up, then I'm here. I came back and I went with the Department of Agriculture in Ottawa first. I did some work there, some interesting work. L.E. Westman was also in Ottawa at the time. We used to meet at meetings. I discovered something in Ottawa that was interesting viz an extraordinarily simple method of separating hippuric acid from the urine of cows, in large yield and cheaply. Well, this discovery got me my job with the Connaught. I wasn't too interested in the actual routine work in Ottawa so I came to see Professor Miller and I showed him a sample of hippuric acid and derivatives some of which were sweet smelling. There are interesting substances which can be made and starting with hippuric acid I made some esters and dyes and dyed cloth. Prof. Miller was impressed, I think. I was thinking of going over to Eastmans in Rochester. He said, "Oh, no, don't go over there, they'd steal the coppers off a dead man's eyes. Then he said, "There's a man here who wants a chemist." It was Dr. Fitzgerald so he recommended me. I think maybe I met him, Dr. Fitzgerald, at that time, I'm not sure. In any case I wrote him a formal letter applying for a job and was taken on right away and I've been with the Connaught since.

W: Well, you were working on your Ph. D. at the time?

M: No, I worked for the Ph. D. after I came to Connaught and it was in the Chemistry Department. It was on a problem concerning Insulin. I had nothing to do with the discovery of Insulin, but I was a witness to what was going on.

W: Yes, well that was the part that I wanted to ask you about. Do you want to talk about that now?

M: Right, right.

W: Tell me specifically where you fitted into that.

M: Well, I came in rather accidentally. I was a chemist, in fact I was the first chemist they had in Connaught and the only one at the time, and there was thought of Connaught taking over the manufacture of insulin. They wanted some extra help in an insulin lab, a purification lab which was in the basement of the old Medical Building, and it was down there that I did some work on preparation of insulin. It was an old rattle-trap place and I remember on one occasion I was very fortunate. There was a glass-stopped bottle of picric acid on a shelf. When a motor was in operation (in connection with the concentration of acetone solution of extracted insulin) the whole section would shake. On this occasion the bottle of picric acid fell to the floor and there was a most violent blast. Picric acid is an explosive and fortunately it was only the small amount of dry picric acid in the neck of the bottle which had exploded. If the whole pound had been detonated it would have wrecked the Lab.

I remember on one occasion Banting came into the Lab to get blood from a rabbit which had been injected with insulin in order to measure its blood sugar lowering effectiveness of an insulin preparation. Well, he struggled for I don't know how long and finally he said, "You try it." It is one of these things that can happen. I got the blood from the rabbit's heart straight off. It was the luck of a beginner. Later I had associated with me Don Findlay. We developed a method for the purification of insulin which came out of work I had done with hippuric and benzoic acids. In the hospital undesirable reactions were being induced by the insulin available and the method we had devised gave a better product. I suppose there were some thousands of doses of insulin purified by the benzoic acid method given. It wasn't the best method but at the time it served a useful purpose.

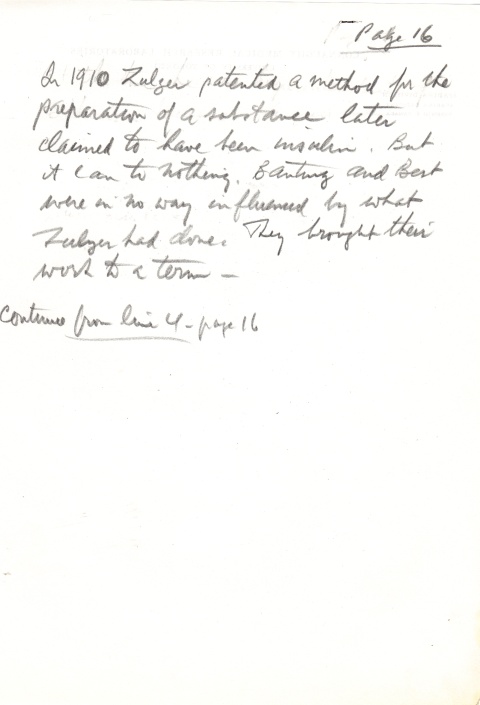

In 1910 Zulzer patented the preparation of a substance later claimed to have been insulin. But it came to nothing. Banting and Best were in no way influenced by what Zulzer had done. They brought their work to a term.

W: How did you first hear about it? Do you remember?

M: Yes I do. Sitting in a -What was the name of the restaurant opposite the City Hall? Bowles. There were chairs, an arm of which served as a table- Professor Eddie Fidler came in, I was in the city. It was in the summer time -holidays.

W: What year? Excuse me for interrupting.

M: '21

M: he said, "They're doing some interesting things up there, there seems to be some interesting results." I wasn't greatly impressed, interesting results are being constantly reported. I had an aunt die of diabetes before the advent of insulin, and in 1921 I was turned down for life insurance on medical grounds. Now I have to say that this aunt of mine was an aunt by marriage, so there was no genetic threat. But, nevertheless, I realized that diabetes was a very serious disease. I was married and had young children and in a sense to be condemned to an early death, for a young man is something of an assignment. I hadn't have any money. I remember I was talking to a friend of mine, a lawyer, Bill O'Brien, great man, an artillery officer (1914-1918), condoling with myself, you know and finally for some encouragement I said, "At least they didn't find any sugar in the urine." He was a light-hearted man, he said, "Did they find any salt and pepper in it?"

So I was introduced early to the seriousness of diabetes.

W: Why, with your particular interest in it, weren't you more interested in it, the day in the restaurant when you first hear about it?

M: I don't think I'd had the physical examination at that time, no, it was a little after I had the examination.

W: How was the news given to the academic community first, and then to everyone else?

M: Oh I think it was given to a skeptical academic community. If people could have foreseen the future they would have been immensely thrilled. I must admit I don't remember. There was certainly on the part of many people a great skepticism, was there anything in it? There always is questioning you know, and rightly so. A finding has to come through to a fruitful end. What does it do? You know yourself the breakthroughs that come. One of the great breakthroughs was cortisone for arthritis. Well it can be a dangerous drug. But skepticism can be a good thing.

W: Did it make a lot of news?

M: Oh yes, once insulin was shown to be a likely treatment for diabetes. And then when there was sound clinical evidence for its effectiveness, there was no doubt at all about interest in it.

W: There were a lot of articles in...

M: Oh, well, the newspapers were filled with it.

W: How long did it last, that kind of excitement?

M: I don't recollect. Even a report on my work came out. Some people thought I was involved in the discovery. I had nothing to do with it. There was the method of purification, you know, but that's how things can be misrepresented.

W: Did you enjoy the whole excitement about it? Did you feel there was too much?

M: I think I was interested in a particular aspect viz obtaining insulin in pure form. That was my interest and practically nothing else.

W: What effect did the discovery have on the attitude to research in the university for a start?

M: That's rather a broad question, the question how did it affect policy, something like that?

W: Yes. Except did people suddenly say "Well, we've had this success. We should put more money into research?"

M: Well, really, I can't say I'm competent to answer that. I am sure it was a stimulus to research. The Connaught was an open place for research from the beginning, before the discovery of insulin. I might express a personal opinion which could be misleading.

W: Did you know Professor MacLeod?

M: Oh, indeed I did.

W: That's one area that I'd like very much to talk about for a few minutes. I understand that he arranged the initial presentation, is that correct?

M: Now there you come into an aspect of history that's rather difficult and somewhat controversial, I think.

W: I know, that's why I wanted to talk about it.

M: Well I tell you. This comes up and I think people take sides. I knew Professor MacLeod. I certainly knew him. For example, one of the things I remember very well was this: Sir Henry Dale from England came over with another man and after we'd had the benzoic acid method for the purification of insulin going, which really wasn't a great thing, but it was something of a novelty at any rate. MacLeod wrote him telling him of our method and Dale wrote back, "He probably got the idea from so-and-so who was with me." Well, there was no hint of truth in the statement. I resented it. No, I don't know. I tell you there's somebody has a very fixed opinion regarding MacLeod, she worked with him - Miss Kathleen O'Brien, Bill O'Brien's sister, later she became a nun, she was in Physiology. She's out at Providence Villa now. She was very much a MacLeod - I was going to say a of a MacLeod man, a MacLeod woman, she was very loyal to him.

W: What sort of person was he?

M: He was as I remember a very pleasant man, a very good lecturer, he spoke well. I didn't know him intimately. You could see my impression was this: There is no doubt that Professor MacLeod was not responsible for the initial idea nor for the initial results, but he was a well-known figure in Physiology and the fact that the work was done as soon as it was in his Laboratory may have been an aid in having it accepted. You know, a thing like insulin could easily have fallen through in the beginning. I remember at one stage when yields were wretchedly poor, Banting was in a frantic state. The step responsible for good yields was extraction with acid alcohol. I don't know the history of this step.

W: Well MacLeod's reputation came under a cloud over the five years.

M: Yes. Well he may have been imprudent. I don't know. Yes, I know it was, but you know it's awfully hard, it's awfully difficult because prejudice can come in and injustice can be done. MacLeod shared in the Nobel Prize. Now, I have no idea whether he should have accepted it or not. I think if he hadn't accepted, it would have made a big difference. It was 'Banting and MacLeod' or 'MacLeod and Banting' I don't know which it was. I think there was some resentment on that score, but I don't know. One has to know almost the workings of people's minds almost to form a proper judgment. It's so easy to be unfair, to be unjust. I remember, I went to see Professor MacLeod before he left. L. E. Westman was editor of a journal and he wanted to have something about the work of MacLeod. Well I interviewed him where he lived in some part of Toronto, Rosedale or some place. I don't know where it was now. It was a very pleasant afternoon as far as I was concerned, and he gave me lists of his publications, the question of the insulin did not come up.

Now another aspect of MacLeod and contribution to insulin was this. Let's assume for a moment that Zeultser did have insulin. There were two reasons for his failure. It was condemned in the clinic, you know, the reactions were too severe. Now, may have been insulin reactions-due to blood sugar lowering or the reactions may have been due to insufficiently purified insulin. I think they could have struggled and gotten adequate preparations if they had stayed with it. And there was no good method for blood sugar determination. Now MacLeod had such method.

W: MacLeod Lab?

M: MacLeod in his lab because it was a physiological lab. And I think he was responsible for improvement in testing. Instead of testing insulin using depancreatized dogs he used normal rabbits, which was a real advance. The use of depancreatized dogs is almost impossibly expensive.

W: So he may have made a contribution to the actual development...

M: Oh, I don't think there is any question about that, Madam, I think he did. I think it was really a contribution. It may have been an essential contribution, you know.

W: M'hm.

M: I don't know. This is where the business comes in about someone said so-and-so, and some said so-and-so and this-and-that. And I think one of the really serious things in life is this business of ruining a person's reputation. I think it is a very serious sin.

W: And his was ruined?

M: I don't know. It was to Aberdeen he went. I know a man who was a student of his in Aberdeen. I think he found him in good spirits. By the way there is a very interesting commentary on the discovery of insulin. It is not serious in respect of insulin but is a caricature of modern research and appeared in a New England Medical Journal, not the New England Journal of Medicine, and very clever it is. It is entitled "It Couldn't Happen Now". The author goes on to say, rather extravagantly that Banting was a drop-out surgeon, a failure, and Best was a student of Biochemistry and so on, and that they only had ten animals and permission to work for only eight weeks, and that they hadn't any computers to work with, or any statistical analyses of results. It was just a total failure. At the end the author says we are grateful it happened then, it couldn't happen now. It is a very amusing article-quite recent (1974).

W: Can we get back for a few minutes to your early days in the lab aside from the insulin and talk a bit about some of the people? Could you tell me a bit about Professor FitzGerald?

M: Yes. My relations with him were always very pleasant indeed. I was the first chemist at the Connaught. What interested Dr. FitzGerald at the time was the production of diphtheria toxin. I remember there was a woman associate, Miss Hanna, a wonderfully fine assistant in the lab and a fine person, and we published a couple of papers, I remember, on immunity. Nearly all my work has had to do with questions concerning immunity and immunochemistry. And it's been a fruitful field. And the field broadened from application to infectious disease to something that applies to a wide range of subjects, viz, pathology and transplants and physiology and enzymology. The list is not complete. I lived through advances in this field. A very wonderful person was Miss Ina Fraser. She afterwards married Dr. Ray Farquharson. We had some interesting work together, some original observations on diphtheria and diphtheria toxoid. Dr. FitzGerald in the early '20's was in France. He cabled back they had something there that was of great interest: an effective method for the prevention of diphtheria. He was interested in diphtheria, in fact, that's how the lab started. Because of the cost of diphtheria antitoxin he decided to make it cheaply available. But antitoxin is not the answer, the answer is immunization, and there wasn't any good method for immunization. But in France Gaston Ramon had come up with the answer, viz: diphtheria toxoid. Well, Dr. FitzGerald cabled that we begin work on the new product. There was a man with me then or came shortly afterward. What was his name?

W: It wasn't Orr, was it?

M: No, he came later. It was a man who afterwards was a Professor of Physiology at Dalhousie. He went through Medicine-Beecher Weld, oh, a great man. Well, he and I worked on this project, I remember that he and I took the first home-made toxoid and I became quite ill during the night. I realized that a drop of toxin could kill several men before it is transformed into toxoid, by the addition of formaldehyde, and that with some chemical systems the reaction is reversible. And I asked myself, does anybody know how to reverse the reaction. Well I came in in the morning and found that Beecher hadn't had a reaction so then we knew that reactions were not due to primary toxicity of the toxoid. I became interested in the problem of reactions and found a simple method of detecting those who would react. But I remember after Beecher Weld, Miss Fraser came about whom I have already spoken and about the same time Edith Taylor. She was a wonderful person. Later during World War 2, she developed a type of broth which yielded tetanus toxin of the highest potency ever produced, toxin which in turn is converted to tetanus toxoid and used for the prevention of lockjaw. It was her work-Dr. Edith Taylor. Mr. Orr was a colleague. He and I, we had an interesting piece of work on reaction of diphtheria prophylactics. I think we solved some questions that hadn't been answered before. During the war he was made head of what we used to call "The Farm" and now it's the Dufferin Division. I still call it the farm.

W: I think it sounds much more attractive.

M: I'm really fortunate here, thanks to Dr. John Hamilton and the University. And the work is interesting still, I mean very interesting indeed.

W: Can we go back for a few minutes to FitzGerald? You talked a little about him.

M: Right.

W: Can you tell me a bit more about how he ran the labs in the early days; what sort of a person he was to work with?

M: Well, for me, I never saw much of him in the lab, that is in my lab. and any dealings that I had were always extraordinarily pleasant. He was, I fancy, rather dictatorial. But with me he was a wonderful Director.

W: Why didn't you see him in the lab very often?

M: Well he just left you alone, that's all. I mean, that was a wonderful thing, I had a free hand. You had to confine work to a general field, you couldn't e.g. work on ingrown toenails, or something like that. There was a certain general field, and in that field you had a free hand, it was a marvellous thing. He became mentally ill toward the end, you know, and he died relatively a young man.

W: Well when you wanted to do a certain piece of research would you go to him and ask for his approval?

M: Well if it were in the assigned field, no. I'd give him results. I'd tell him about results. I mean, the best way of gaining approval is talk about results, and I think he was sufficiently impressed with what was going on. I'm quite sure he was from the things he used to say to me. And I think he may have been constrained by the feeling he wasn't a chemist.

I don't know how much French Dr. FitzGerald knew. He had spent time in France and Belgium and Germany. On one occasion there were visitors coming from France and he came to me and said "I want you to meet these people at the station, you speak French, you were at St. Michael's College." Being at St. Michael's College didn't imply knowing French. But I thought, O.K. I'll not let the College down. I do speak French now but not then. It was a terrible assignment, I was in real difficulty. I did go to the station and meet the visitors and was able to say sufficient to direct them to where we had to go but I wasn't really talking French. Two weeks notice is not enough in which to learn a foreign language. Later on I didn't see too much of him. He was away a good deal and he wasn't well. I remember once after he'd been away, he came back and he came into my lab. I told him what I was doing. He said, "I want to make up for lost time." And I said, "Doctor FitzGerald, you should never think of that. This is wonderful of you to come round and talk to people in the labs. And it is too, to have someone who will listen intelligently and sympathetically to an account of what a man is doing.

W: And he did do that?

M: No, he died rather shortly afterwards. He died not too long after that.

W: Could you explain to me, despite having read Dr. Defries' book, I still find that the relationship between the Connaught labs and the School of Hygiene very confusing.

M: Yes. In the early days of FitzGerald there was the Department of Hygiene and he was, I think, named Professor of Hygiene, FitzGerald was. Well he became concerned about lack of antitoxin for treatment of Diphtheria. One wonders sometimes how good it was anyway, but I'll tell you there is an authentic story about that lack of antitoxin, a terrible story. It was told by a friend of mine, a Newfoundlander whose father was a magistrate. In some small community there were two cases of diphtheria in a family. Antitoxin was expensive. The doctor came, and diagnosed the case and said to the mother, "Which one do you want to live?' Well, what a question! And the mother had only money enough to pay for the treatment of one child. Now this child lived and the other died. The doctor had to get out of the community. The father of the man who told me the story , who didn't know medicine, got in a supply of diphtheria antitoxin and would inject it in a case of diphtheria, a risky business for him. Regarding the question of effectiveness of the antitoxin, there are some interesting statistics from the first decade of this century, that's before you were born, Madam, you know. In the first decade of this century at the Isolation Hospital here in Toronto, there were cases of Diphtheria treated with antitoxin and cases not treated with antitoxin. With those treated with antitoxin, there were significantly more deaths that with those not treated. Now mind you that doesn't prove or disprove anything, regarding the usefulness of antitoxin. It is my guess that because antitoxin was in short supply or expensive what were judged to be mild cases were not treated with antitoxin and severe cases were. An animal given diphtheria toxin will die if the administration of antitoxin is delayed beyond a certain time. Coming back to your question, Dr. FitzGerald when Professor of Hygiene, had the idea of supplying antitoxin either at low cost or free of charge. From this idea came the Connaught. So the Connaught was from the beginning, one could say, part of the Department of Hygiene. And later the School of Hygiene. Well, during the First World War there was a need for tetanus antitoxin and property and building were donated by Col. Gooderham. The Duke of Connaught, the Governor-General at the time, came for the opening ceremonies and the Laboratory was named for him. Connaught grew to be a large institution. Dr. FitzGerald was still Professor of Hygiene and when the School of Hygiene, at his instance, was built he became Director of the two institutions. That tradition was maintained by Dr. Defries the second Director. Having one Director for the two institutions was advantageous since members of Connaught, some of whom held teaching posts in the School of Hygiene, were engaged in research on products that were useful in public health.

W: Because the Connaught lab was a ... really a business, to some extent?

M: In part, it was.

W: Did it cause any resentment around the university?

M: Oh, I don't know. I think there was some resentment because I've heard the Connaught referred to as the factory with some contempt it seemed to me. Well, of course this is all nonsense, I mean it might not be the place for it in the university, I don't know. I don't see any very grave objection because I fancy the university for their research funds will take money that's derived from industry without any hesitation, interest on anything and grasping for it and I can't see any reason why money made from work carried on in the university is unacceptable. Concerning this question of money: some years after the School of Hygiene was built the Rockefeller Foundation had an office in the School of Hygiene occupied by one of their men who was responsible for the distribution of funds, Rockefeller funds. Rockefeller had given a good bit of money for the building of the School of Hygiene. I remember the lunch given. There was a luncheon in honor of the first Rockefeller representative. President Cody was chairman and there were about fifty or so invited guests and all there grasping for Rockefeller money. A great honor was to be given this man. I walked down University Avenue with Dr. McIntosh, the Rockefeller Representative to the Alexandra? not sure of the name, where we had lunch. I was very much embarrassed when the President stood up at the end of the luncheon and began by saying "If there can be such a thing as tainted money it can be redeemed." Rockefeller money was thought in some quarters to be tainted. On returning to the lab I felt I must apologize for what the President had said. Dr. McIntosh then said, "It didn't bother me any. I was thinking of what Mark Twain had said about tainted money. He said, "All I have against tainted money is "taint yours and taint mine"." If ever there was clean money, it was Connaught money. We were never paid much and we did honourable work, we worked hard. I resented very much any downgrading of the Connaught.

W: Speaking of money.. I'll just ask you one question, and then we'll have a break. Did people in the lab suffer financially during the Depression?

M: We had our salaries cut, you know. We had a 10% cut in salaries. I don't think anyone suffered. But there was lack of money. Oh I remember the lack of money. There was a disastrous flood in China. Dr. FitzGerald was a member of the Health Section of the old League of Nations and it was planned to send out a team to China. (tape went off here)

Well, what I was saying was that Dr. FitzGerald was a member of the Health Section of the Old League of Nations and there was a proposal that following the flood in China, a team be sent out to study certain possible consequences which might follow the flood, e.g. diseases such as cholera, plague, typhus. Dr. FitzGerald talked about this a good deal. He'd bring it up at lunch time for example. I said to my wife "You know, I think he wants some one to go to China." This was during the Depression. Well, I had a small family, I had no money to speak of. So anyway, we decided at home it might be a good thing to do for my future. I went to Dr. FitzGerald and said I was willing to go. He was delighted, the very thing he wanted. So he phoned Ottawa and told them that a Connaught man could be a member of the team. Well, I think the country from which a man went had to support him. I think it would have required something like $5,000. They wouldn't put up a plug nickel so I didn't go.

W: You must have felt disappointed having decided that you would go.

M: Well, I just accepted the decision. I did know some people in China. I also knew the Director of a Japanese Biological Institute in Manchuria. I was going to go there first to see him because he would know a good deal about Asiatic Diseases. I even had a scheme for immunization against typhus. It would have been a great experience for me.

W: Did you see President Cody very often?

M: Not very often. I think there were two or three occasions. He called me in once and asked me who I thought should be the next Director - after the death of Dr. FitzGerald. I didn't think it was a serious question, I thought it was sort of a manifestation of democracy in the sense that the decision was already made but that we would just go through the form. Maybe I was wrong. He was a classmate of one of the men at St. Michael's - Father M. V. Kelly and I remember asking Dr. Cody about him. Well, you knew right away, he answered: Michael Vincent Kelly.

W: Did you know Falconer at all?

M: No, I didn't know him. I doubt whether I ever spoke to him. By the way, Professor Ramsey Wright, I was told, left Toronto rather in a pout because he wasn't made President after Falconer but that may be unjust.

W: Another person that interests me in reading about the early days of the lab was Colonel Gooderham, who seemed...

M: Yes. The question brings to mind an incident which has to do with Col. Gooderham. Gaston Ramon, Director of the Pasteur Institute, during the War and a friend of mine, discovered diphtheria toxoid for the prevention of diphtheria, and tetanus toxoid for the prevention of lockjaw. He was visiting the Connaught and was guest of honor at a dinner at Colonel Gooderham's house. What I remember of the event was this: after the dinner Col. Gooderham said, "Gentlemen, would you like some 1886, or some 1874 whiskey?" I remember I said '74 because I thought I'd never have a chance in a million years to have it again.

W: No. This interests me to know why he was so interested in the lab.

M: Well, I'll tell you what it was in part. You see, he'd been engaged in the distillery business and I don't think at the time he was actively engaged in anything, I'm not too sure about that. I don't know how active he was as a Colonel, but he had a great sense of loyalty. Here was something that was needed - tetanus antitoxin in World War I. Colonel Gooderham supported this cause most generously in terms of property and money.

W: He must have been a very useful man of course for Professor FitzGerald at the beginning of the lab.

M: Oh yes he was. I didn't know him at first hand. He was really a very fine man, I'm sure.

W: Is this business of people being credited for research such as we were talking about with MacLeod, is that a real problem?

M: I don't know. One hears of this kind of thing. Certainly research is shared. I think it has to be. And I don't think this presents a difficulty.

W: No.

M: Research is shared. But to have someone sitting as a kind of image at the top who would take credit for something that was done, and who didn't know anything about the subject, I doubt this happens often.

W: Did it happen to you?

M: No. It's something I wouldn't want to let enter the threshold of my consciousness. I had to give a couple of interview in French on the French station here. That's a tougher thing than talking to you Madam. I speak French but it isn't my language. There was a new lab opened at the Dufferin Division and this was to be the subject of the interview. An unexpected and awkward question was asked me: Do you think there's too much money spent on medical research?" There will be waste. There can be great waste in research. It may not be eventual waste, but I tell you what, waste comes in in this way. Certainly all the results, all the observations made, all the things done, don't come to publication and this can be waste and even the things that are published are sometimes of little or no significance. I think I said, in reality, no. I think this was a correct answer. I didn't want to get my head chopped off after I left the place.

W: No. Did you ever have any interest in going to work somewhere else outside Toronto. or outside Canada?

M: Oh I spent a bit of time, I spent some time in a physiological laboratory in Belgium and another time in a chemical Lab in Germany but it was only for some months. You mean, give up work here?

W: M'hm.

M: No, I didn't. I had a chance. I had an offer of a job with the Squib Co in New Jersey. A man from Squib's came and asked for me. I said no and I'm awfully glad I did. It was this - if one were cramped in what one was doing and there was a great lack of freedom, then I think one would want to leave.

W: But you never had that.

M: Oh, I never had that at all, not at all! It's been a great privilege for me to be here and for so long.

W: Can we go back and I would like to ask you a bit about Dr. Defries.

M: Dr. Defries, Dr. Defries..

W: When did you first get to know him?

M: 1919. I didn't know him well as a person. But I can tell you one thing about Dr. Defries. I think from some points of view he was an extraordinarily good Director, not in the sense of telling what research has to be done, but in the sense of the overall running of the place. He was a man very keen about keeping the two institutions under one Director viz the School of Hygiene and the Connaught Labs. I personally was rather indifferent about this. My work was what interested me. I wasn't interested in university politics concerning this matter. Dr. Defries was. He saw that funds were decreasing. He was a good economist and he kept things in good shape. He had many good qualities. I remember once Dr. Defries came between Christmas and New Years and told me that Mr. Bickel wanted to give money for research. I suggested some work on the possible effect of heparin on cholesterol induced plaques in arteries. Thanks to the money we had the opportunity to do the work. Our results were negative. Bickel funds were then used for a project on the antigenicity of insulin which yielded very interesting and useful results.

[Page 40-41 omitted section about cholesterol experiment]

W: When did that money come, do you remember?

M: About '52, and '54 or '53 I began this new work on insulin which turned out to be very fruitful.

W: What went on in the lab during the war aside from vastly increased production? Was there any war research being carried on?

M: I would have to say there was research as for example on phases of the preparation of vaccines and there was the work of Dr. Edith Taylor on the production of a medium suitable for the production of tetanus toxin used in turn to make toxoid.

W: Was any of it secret?

M: I don't think so. I am just trying to recall any secret work. I don't think so. One of the jobs I had was in connection with anti gas gangrene serum which I think now may have been useless. But great quantities were prepared. There were three different types. And it was important that no mistakes be made in the identity of type of antiserum or antigen used for its production- a great number of horses were used for production of antiserum. Even the racing stables at Hamilton were used as extra housing of horses. I had a very good set-up for testing so that the possibility of mistakes was minimal. Fortunately there were no mistakes. There was quite a number of girls employed on this work. Speaking of secrets: during the war two men from Russian came to the lab. One spoke english. And we were told to answer any question they asked, no secrets. When it came my turn, I asked "Are you concerned in Russia with the production of anti gas gangrene serum. Do you produce it? "Oh yes, we do in Russia." So I told them in great detail our methods which they wrote down. And then I said, "Now, how do you do this in Russia?" Well, there was no answer. And then I said, Now maybe you didn't understand me so very clearly I restated the whole thing and then there was some Russian snapped from one to the other, they walked out of the room. Terribly bad-mannered people.

W: You think they were...

M: If I had my way, I wouldn't have told them anything, that's all. You can easily deal with secrets. You can say, "Well, look we can't tell you that." You can be honest.

W: But there were no problems of publication or anything during the war?

M: No, no, not that I know of. I remember I published in English journals methods for the purification and testing of tetanus toxoid.

W: Did you ever work out at the farm, or have you always been down here?

M: No, I never worked there. No, I go there every so often now, you know. And it's rather a nice place to visit. It's a little far off. You can go by common carrier but it's pretty slow.

I never worked at the Farm. I remember Dr. FitzGerald wasn't well. He'd been away and when he returned he helped Mr. Orr at the Farm. I went out to ask Dr. FitzGerald something and he said, "Why don't you come and work here?" It was a few weeks before he died.

W: I would like to go right back to the very beginning for a few minutes and talk a little bit more about your time at St. Michael's because it was so interesting.

M: Okay, okay.

W: What sort of rooms did you live in? Did you live by yourself? Did you share?

M: Well, at one stage as high school boys we lived in common dormitories, several beds in a room and we had to get up at 5:30 in the morning even in winter. And there weren't individual showers or toilets. There were facilities, but they were common. You tend to forget the past. One thing they had at St. Michael's a very good experimental lab. I was able to go there and do some work. That's what really got me interested in the work I do. It was not part of my undergraduate course, you know. I remember around 1910 I assembled with the materials available, a simple outfit with which you could send a wireless signal, and I could ring a bell in the next room, without any wires attached, a tremendous thrill. And I remember very well it cost me 10 cents because for one stage you had to have a mixture of nickel and silver filings. Well the nickel I got from an American nickel which I destroyed, and the silver from a Canadian 5 cent piece which I destroyed. I remember there was someone who had a French book on Physics from which I learned that tape recording had been done in France certainly in the first decade of this century. It was an elementary device and reproduction was faint. What really made tape recording feasible was advance in electronics. One of the old priests, a Canadian had done his novitiate in France in the town not far from Lyons, always reminds me of the Montgolfier brothers from Annonay, who were the first to make a balloon capable of taking a man up. A few days ago I saw on the front campus a balloon ascending with a man in the basket - the balloon was held by a length of rope. Well this old priest taught us French. He was a marvellous teacher, a classical scholar. The book we used was called Lecons Des Choses. I remember it was in high school. It was the one year I had in high school there, and from time to time in class we tried to turn him off the French by asking a question in English. It might be something that came up in Lecons Des Choses, you know and he would tell us interesting stuff. He told us one time about the chemical laboratory course they had at Annonay. They had no gas or electricity, heat was from charcoal with an air bellows. And the boys wore leather aprons and a whole day once a week was spent in the lab. The man in charge of instruction was a man from the Polytechnique in Paris, a contemporary of Pasteur. They did things there that no laboratory does now. For example, they would make elementary phosphorous from bones got from the kitchen. I mean phosphorous, that would take fire from the heat of a finger. Well, years afterwards he died in the '30s. I talked to him - by that time I had a little bit of sense - asked when did you do the lab work in Annonay? And he said simply before the war. It was the Franco-Prussian war, 1870.

W: What was the man's name?

M: McBrady.

W: One thing I wanted to ask you when we were talking about your early days in the Connaught Labs was how you got your Ph. D.?

M: You mean "how"?

W: Yes. You said you were doing it while you were working.

M: Yes. Well, I was registered, you see, for a Ph. D. and I had underway a rather good piece of work.

W: Who was your supervisor?

M: Well, the people in the Chemistry Department. I remember, Miller and Allan at the final Ph. D. examination.

W: Well, were you still working for Professor Kendrick?

M: No, no, that was earlier.

But I kept up my contact with Prof. Kendrick. When I came to the Connaught it happened that I was the first in Toronto, I think, to make pH measurements by an electrometric method, I had to assemble my own potentiometer and to make my own electrodes. I devised a small electrode, a new type which was very rapid in action and I remember I went to Professor Kendrick who was a good glass blower and asked his help in making the electrode, which he generously gave.

Miller was much taken with the idea of the electrode. (Dr. Miller would call Dr. Moloney "pH Moloney".) This was before registration for a Ph. D. But it think it helped me when my Ph. D. work was underway.

W: Who approved your thesis topic for your Ph. D.?

M: The people in Chemistry.

W: It wasn't one individual, it was done by a group?

M: Well it could be, I suppose, Miller would be the man.

W: Did you see him very often while you were working on it?

M: No, I didn't. I would see him once in a while. This was one of Kendrick's ideas, I think, that you mustn't guide a man too much.

Kendrick it seemed to me was a man who was frightened of explanations. I was the only person from the university at Kendrick's funeral. The night before I was at a dinner at the University Club and someone said Kendrick's dead, and he's going to be buried tomorrow from St. Batholomew Church, I think it was, in Montreal. So I rushed home and told my wife and went down to Montreal that night. I was very glad that I had gone because at the graveside, I could speak to Mrs. Kendrick. There was Mrs. Kendrick, her married daughter, Mrs. Wells and their son. I had never met them before. I told Mrs. Kendrick what I thought of her husband and she said, "Will you tell my grandson just what you said to me now?" I was very glad that I had gone to the funeral.

But, coming back again to this business of the Ph. D. and Professors of Chemistry, they more or less left me alone. This was policy. Their question was, what are your results? That's what they were interested in.

There was a meeting of the American Chemical Society in Cincinnati in the early twenties at which I gave a paper on an aspect of the chemistry of insulin. Miller was in attendance and commented favorably. I think this helped in acceptance of my Ph. D. thesis.

W: How long did it take you to finish it?

M: Oh, 3 or 4 years something like that, I'm not sure of the length of time.

But coming back to this question of theory, Kendrick was criticized because he didn't talk about molecules and atoms. He did talk about reality and the interpretation of reality. He wasn't opposed to theory, but he was afraid that theory might drive one into a position which could lead to doors of investigation being closed. Even such a venerable doctrine as evolution can be misleading. I'm not talking about religion. Suppose for an investigation concerning e.g. the treatment or prevention of a given disease or the safety or efficacy of a drug etc. We require a species of animal closely related to man. Which is the species? A question which demands a second. Closest in what respect? If insulin is in question, it could be the pig. The insulin of the pig and of one type of whale are more nearly identical with human insulin than that of any other species so far investigated. Apes of any species are not necessarily suitable for the study of a given human disease.

I thank the men of the Chemistry Department and in particular Professor Kendrick.

I had a small Department with a small budget, not enough money to buy a certain apparatus. At the end of the year there was a balance which could not be added on to the next year's budget. With the balance I made a partial payment for the apparatus we needed and paid in full when funds for the next year were available. Kendrick was in no way personally involved but he didn't approve of what I had done and he was probably right.

W: Dr. Moloney, are there any questions, or areas that are particularly interesting to you that I haven't asked you about? Or any people that you were particularly impressed with and I haven't questioned you about?

M: I don't think so. I don't think It's so much interest the people of later life, you know, that have been with me, associates. Good people, you know. The other thing is that my experience in life have been this, Madam: that everybody that I've worked with turns out to be a good person. I mean it's an odd thing. And I can't look back and say well here was somebody, something I don't want. That's not what it is at all. And I think, I'm not so sure that maybe that's the experience of everybody, I don't know. But that's my experience.

W: I think it depends on your attitude.

M: Beg your pardon?

W: It depends on your attitude.

M: I suppose it does. I don't know. Some marvelously talented people that have been associated with me, you know, and I mean they have had limitations as I have had. I mean there's no doubt about that.

W: What research are you doing now?

M: Well, it is still on questions of immunology. The recent work came out of a study of the antigenicity of insulin. For a long time it was generally thought that insulin was not antigenic, that it would not induce antibody formation and resistance to the action of insulin. And there was good reason for this opinion because there were thousands and thousands of diabetics were receiving daily doses of insulin and on the whole requirement of insulin did not increase. When it did it was generally thought that immunity was not in question.

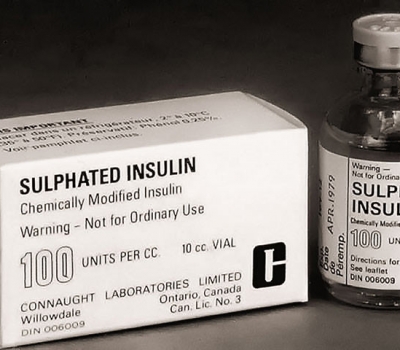

Certain investigations had presented evidence indicating that insulin is antigenic. As a problem for a graduate student, I suggested that the possible antigenicity of insulin be re-investigated. This work along with the work of Louis Goldsmith and Marie Aprile yielded results which demonstrated conclusively that insulin is antigenic and that resistance to the action of insulin can be an immunity phenomenon. The work eventually led to the production of a chemically altered insulin which is useful for the treatment of diabetics who develop high antibody-type resistance to insulin. This latter work was done in collaboration with Marie Aprile and Strathearn Wilson.

There was a man, a friend of mine, Jules Froynd, he had a certain thing called an adjuvant. You mix it with an antigen and it enhances the antigenic value. And then I wanted to make a certain kind of test for antibody, or for immunity response, and the guinea pig was the suitable animal for that sort of thing. Well, right away, the results came right away, that it was anitgenic, and that guinea pigs developed in a very high degree antibodies to this thing so that , at the beginning, so much would affect the guinea pig and lower the blood sugar, after a while it took tremendous amounts to lower the blood sugar, you know. And not only that, it took the serum from these quinea pigs, take the blood and get the serum, and this serum would, if mixed with insulin would neutralize it, you know. And if you injected this into a mouse, for example, neutralize the insulin of the whole mouse and the mouse became diabetic at once. And this is really, a very thrilling thing for me, you know.

W: It must have been worrying though.

M: I beg your pardon?

W: It must be worth worrying if a lot of people were taking insulin...

M: But they weren't developing resistance.

W: They weren't?

M: But once in a while. No, no, it doesn't happen, because it happened. There's another reason for that, that I found out later on. Now it's.. But it does, some people do. And at this time, or shortly afterwards, then they found out that quinea pig insulin with the antibodies you get, you couldn't neutralize it, you know. But if you immunized a horse, the serum would neutralize the insulin of the rabbit, [and the guinea] and the mouse, and the sheep, and a whale, and human, and monkeys, and a whole... and heifers, but not guinea pig. Guinea pig stood by itself. And in fact, in the phylogenetic scale of mammals, you know.. This is another thing about this business about evolution, you see. There is a tremendous... There's a great similarity between insulins from a mouse to the whale, including humans, but those mammals, guinea pigs and the like of them, they are just in a different order. As a matter of fact, in respect of insulin, we're more closely related to some fish than we are to guinea pigs, you know. I mean, this is the interesting thing.

Well, there was a woman came up, Dr. Ezran had a case in the General Hospital. She developed a marked resistance, so her serum would neutralize this and this and this in a very marked degree. Well, poor woman, she had one leg off and the other foot going bad thanks to the diabetes, and it couldn't be treated with insulin. And, oh gosh, we felt badly about it. So, anyway I went on looking. Well, we found cod fish insulin is not as easily neutralized as pig or beef insulin or ___(?) insulin. But then you don't quit because you develop antibodies to that; but we went on making chemical studies at the same time altering, you see, and one of the alteration was putting in sulphate groups, but that's an interesting thing, and that turned out to be useful. It wouldn't develop antibodies as easily at all and that it would be effective in the face of high antibodies. Well, one of the first cases is a man in Vancouver. The doctor phoned me and we had some available and this man wasn't treated by 1500 units a day, and the doctor said to me "he's got lithrocytic leukemia". Well, I thought, "Well, it's a terminal case anyway", so I sent the stuff out and very quickly he got him under control and then the leukemia was better. Now I think that was an accidental thing. But he went on and he was finally on small doses of this insulin. He was back at his job. And I went out last year or so and I thought he died, when at nine years later or something like that, he died of leukemia in the end. But, there's another case in St. Mary's Hospital in London. Some woman, 4,000 units a day, and something like this. Well, it was a small, a small usefulness but apparently it's there. Well then I became interested in this problem. Could you render an animal such that he couldn't develop antibodies? Well, we were able to do that with the guinea pig, against insulin. He's normal in every other way because you have to be normal, because otherwise you will fall prey to disease. You can do that by giving chemicals, you know such as they do in transplant cases. But this with the guinea pig, it's very interesting, you know, and this kind of aspect by making a certain chemical alteration in the molcecule and giving that to an insulant guinea pig, then he , he's very, oh, he might get all the spurs. If you didn't do that, he would be like that. Well this way he can't get any better than that you know. He keeps very very low and that's interesting.

W: And you're still working on that?

M: Oh yes, oh yes. I mean it was that kind of thing, there is no end to it Madam. I mean, this kind of research, you know, all it does is extend the horizon of ignorance, you know. You're doing something, and more questions come up, you know. But I'm fortunate because I'm an old man and am still able to go on you know.

W: And you're obviously enjoying it.

M: I beg your pardon?

W: And you're obviously enjoying it.

M: Well yes, yes. Yes, it's fine. I don't know how I get support from M.R.C. or how long they'll keep it up, I don't know.

W: Thank you very much, Dr. Moloney.

M: Thank you, Madam.